|

By Grant Merrill, PhD Student

A student once confided in me that he doesn’t follow politics because “it’s all bullshit.” Taking his meaning perhaps too literally, I told him that “yes, by definition, political communication is chock full of bullshit.” My student may have just been looking to vent, but I saw this conversation as a teachable moment. Bullshit, I told him, is actually an academic term with a scholarly definition. Sometimes we think of bullshit as a type of lie, but lying and bullshitting are actually quite different, especially in politics. Bullshit is the dissemination of information with rhetorical purpose but with a disregard for truth. While bullshit can be deceptive, it is not the same as lying. A liar knows (or thinks they know) what is true and seeks to cover the truth. A bullshitter, on the other hand, does not know, or even care, if what they say is true. It is common to deride politicians for lying, but a much bigger threat to democracy today is bullshit. A bullshitter’s goal is to say whatever it takes to serve their own purpose. In a light-hearted example, I might boldly claim that I bake the best biscuits in the state of Alabama. This lofty statement is impossible to verify. It technically could be true, but it almost certainly isn’t. My biscuits are indeed pretty good, but I’ve never submitted them to any baking competitions, nor is my recipe published anywhere. Regardless, many people would likely view the statement as intentional hyperbole. The goal of the statement is not to say with any degree of accuracy that my biscuits are the best; rather, this big biscuit energy presents me as a “serious baker.” In this example, I have no interest in the truth, only an interest in how I am perceived. Likewise, a politician may claim that they would have won reelection in a landslide if not for rampant voter fraud, or that a potentially incriminating phone call that they made was “perfect.” Sounds familiar…Again, such statements may be objectively false, but the bullshitter does not care. In contemporary usage, bullshit is perhaps most comprehensively delineated by philosopher Harry G. Frankfurt in his 2005 book On Bullshit. To build his definition of “bullshit,” Frankfurt draws on Max Black’s definition of “humbug,” a close synonym of “bullshit.” Black defines “humbug” as “deceptive misrepresentation, short of lying, especially by pretentious word or deed, of somebody’s own thoughts, feelings, or attitudes” (Black 143). For Frankfurt, the most salient component of Black’s definition is “short of lying.” While bullshit, humbug, and lying may all involve misrepresentation, they are distinguished by intent. As Frankfurt explains, “a person may be lying even if the statement he makes is true, as long as [they believe] that the statement is false and intends by making it to deceive” (8; emphasis added). Humbug, on the other hand, is “short of lying” in the sense that the speaker does not necessarily intend to falsify what they believe to be true. Thus, an essential feature of lying—and one that distinguishes it from bullshit and humbug—is the intent to deceive. Bullshit does not comprise the essential traits of lies as stated above. A given utterance need not be false or even intended to be false to be considered bullshit. The essence of bullshit is not the misrepresentation of truth, but rather the misrepresentation of the speaker’s motives. As Frankfurt explains: "The bullshitter may not deceive us, or even intend to do so, either about the facts or about what he takes the facts to be. What he does necessarily attempt to deceive us about is his enterprise" (53-54). To elaborate, we might think of both the liar and the bullshitter as attempting to convince their audiences that they are speaking the truth. But while the liar knows (or thinks they know) the truth, the bullshitter communicates without regard for what the truth actually is. The bullshitter is instead focused on advancing their own agenda. This purpose varies depending on the situation, but it is less about the message and more about the speaker and the audience. Bullshit is a means to an end. In the wake of the 2016 United States Presidential Election, some scholars of rhetoric viewed Donald Trump’s ascension to the White House as a watershed moment in post-truth politics. In 2017, rhetoric professor Bruce McComiskey published a lengthy essay titled Post-Truth Rhetoric and Composition. McComiskey begins his essay by calling out Trump’s use of unethical rhetorical strategies, namely “alt-right fake news, vague social media posts, policy reversals, denials of meaning, attacks on media credibility, name-calling, and so on” (3). McComiskey’s essay includes a chapter that explains bullshit in the rise of what some scholars call the post-truth era. While he quotes heavily from Frankfurt, McComiskey reminds us that Frankfurt’s On Bullshit was published long before the 2016 election. McComiskey argues that bullshit has evolved during that time: "Bullshit succeeds only if it, first, convinces audiences to accept bullshit as if it were truth and, second, manipulates audiences to misunderstand the motivation of the speaker. This is where pre-post-truth bullshit differs from post-truth bullshit. In post-truth bullshit, even the audiences have no concern for facts, realities, or truths, thus relieving speakers from the need to conceal their manipulative intent" (12; emphasis added). McComiskey’s point seems to be that political bullshit has evolved beyond a speaker-centered model. In a “pre-post-truth” world, we thought of bullshit as an extension of the speaker, but in a post-truth world, the audience is complicit in the bullshit due to their own disregard for veracity so long as the message is ideologically favorable. Unpleasant though it may be, the stank of bullshit will probably linger despite our efforts to neutralize it. It is not enough to merely expose the inaccuracies of bullshit statements. While the use of fact checking resources such as Snopes has become commonplace, as has the practice of live fact checking presidential debates, these practices may be counterproductive. In particular, the far-right has successfully propagated the myth that they are victims of a liberal media that silences conservative voices with its relentless fact checking. Confronting a bullshitter with their inaccuracies doesn’t work because for them, the accuracy of their message was never the point. Bullshit serves to establish and maintain an identity, so they might treat any fact checking attempt as an attack on their character. They make the conversation about them instead of the message. Communication scholars who study deception often focus on improving lie detection accuracy, but this approach is more complicated with bullshit. Because of the name we have given it, bullshit may not be taken seriously; however, it is an epistemological threat that I feel warrants additional research. By Gil Carter, Ph.D Student

It's the most wonderful time of year. No, not the holiday season, but the ELECTION SEASON! With the 2022 midterms days away, I will provide a brief overview of an impactful but underrated campaign tool: physical mail sent to voters via the U.S. Post Service. You’ve Probably Got a Lot of Mail If you live in a state or district with a competitive election, your mailbox has likely been full of political ads. Even though we see a proliferation of political mail in campaign busy seasons, fascinatingly, the content and effects of political mail are understudied (Benoit & Stein, 2005; Doherty & Adler, 2014). While physical mail is charmingly old-fashioned compared to the ads that cover our social media feeds, mail provides a number of unique benefits to political campaigns, including its ability to target voters individually, opening the opportunity to campaign to people based on specific characteristics, such as voting history, race, ethnicity, age, or residence (Binder et al., 2014). For example, many voters are unaware that their voting history is public record. Thus, campaigns and interest groups can take the contact information of everyone who voted in a party primary and send voters mail accordingly. For instance, if you vote in the Democratic primary reliably in Georgia, you are likely getting mail supporting Senator Raphael Warnock and Stacey Abrams and criticizing Herschel Walker and Governor Brian Kemp. Your neighbor, a non-voter, might get no mail, as they are not on lists of prospective voters. Thus, parties and interest groups can make sure their money is spent on ads to motivate partisan voters to turn out for their candidates. Around election season, it is understandable that people think ads are trying to change their votes, and many of them are, however, many ads are simply reinforcing messages and reminding people of commitments they already feel rather than trying to persuade them to hold a totally new opinion. Compare this highly audience-centered approach in mail to a TV or radio commercial. Anyone, regardless of party preference or voting history, can see/hear those ads, meaning that campaigns effectively waste some money paying for ads that go to people who will not vote or will not vote for the candidate under any circumstances. Further, mailers can be sent to particular addresses, so they can account for gerrymandered or strange districts by only sending mail to the addresses in the district. Other kinds of ads cannot account for these messy district lines, as voters in one district are likely to see/hear TV, radio, and social media ads for elections in districts in which they do not live. Additionally, don’t forget the most obvious (and frustrating) benefit of mail. Unlike an ad on your social media, radio, or TV that you can ignore, when you receive mail, you must do something with it. Even if you throw it away, you still must quickly examine it to determine that it is disposable. Mailer creators know this, so they try to insert items, such as striking photos or memorable quotes, that will stand out even if you determine the mail is garbage. Even emails, which can be personalized in many respects, are not only less tangible, but they can be blocked by the receiver and/or caught by a spam folder. Of course, there is no spam folder or other way to stop the reception of unwanted physical political mail. New Research In response to the research void on mail, I conducted research on mailers in eight U.S. Senate elections and found they tended to use a combination of logical and emotional appeals in each mailer. For instance, a mailer from Maine featured the state’s longtime prominent Senator Susan Collins sitting on a mountain of cash. The text beside the photo of Collins, which had footnotes indicating sources for the information provided, detailed how Collins supposedly took money from special interests. Thus, a Mainer’s eyes would have been caught by the startling image of Collins and then drawn to the “facts” beside the picture to explain the supposed accuracy of the image portraying Collins’s corruption (Carter, 2021). UA Assistant Professor Dr. Josh Bramlett and I are conducting a study on mail in U.S. Senate races going on now, and we have received mail from Florida, Georgia, Nevada, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania, close states in each party’s search for a Senate majority. The current Senate is divided 50-50, giving the Democrats the narrowest majority possible, as they get Vice President Kamala Harris’s tie-breaking vote. Therefore, much is on the line for both parties, as Republicans hope for a net gain of only one seat to give them the majority, a typically attainable goal with a president in office from the other party who’s unpopular in swing states as President Biden currently is. Nonetheless, Democrats see the gaffes of the Republican nominees as helpful to their maintenance—and possibly the expansion—of their Senate majority. So, especially with the stakes as high as they are, as you are receiving these mailers, think about how they are trying to influence you—through your head, your heart, or, as my study found, some of each. References Benoit, W., & Stein, K. (2005). A functional analysis of presidential direct mail advertising. Communication Studies, 56(3), 203–225. https://doiorg.libdata.lib.ua.edu/10.1080/10510970500181181 Binder, M., Kogan, V., Kousser, T., & Panagopoulos, C. (2014). Mobilizing Latino voters: The impact of language and co-ethnic policy leadership. American Politics Research, 42(4), 677–699. https://doi-org.libdata.lib.ua.edu/10.1177/1532673X13502848 Carter, G. (2021, November 18). Persuasion through Voters’ Mailboxes: An Inspection of Mailers from the U.S. Senate Elections of November 2020 [Conference Presentation]. National Communication Association 108th Annual Convention, Seattle, Washington. Doherty, D., & Adler, E. S. (2014). The persuasive effects of partisan campaign mailers. Political Research Quarterly, 67(3), 562–573. https://doiorg.libdata.lib.ua.edu/10.1177/1065912914535987 By Mackenzie Quick, Ph.D. Student If you recognize the phrase in this blog post’s title, odds are that you have a TikTok account. The mobile app, which uses trending sound bites like this as a primary consideration for content creation, started gaining popularity during the initial COVID-19 lockdowns. Since then, its user base has continued to grow, now with a reported one billion monthly active users. According to reporting by The Guardian, “TikTok is on track to overtake the global advertising scale of Twitter and Snapchat combined this year, and to match mighty YouTube within two years.” This rapid progress seems to have caught the attention of Meta, which has seen steady declines in user engagement across its two largest platforms, Facebook and Instagram. While Meta is still dominating the social media market with 2.9 monthly active users on Facebook and around one billion monthly active users on Instagram, it is now more obvious the extent to which the company views TikTok as a threat.

Facebook's tactical smear campaign has continued to purport that TikTok is dangerous on account of its Chinese origins. This was a premise first spouted by former President Donald Trump, who briefly considered banning the app in the United States. The Washington Post received internal emails from Targeted Victory employees that contained comments like, “while Meta is the current punching bag, TikTok is the real threat especially as a foreign owned app that is #1 in sharing data that young teens are using,” and “Dream would be to get stories with headlines like ‘From dances to danger: how TikTok has become the most harmful social media space for kids.” Headlines detailing TikTok trends like slapping school teachers and vandalizing school property soon appeared, prompting attention from United States government officials.

While campaigns of this nature are not necessarily new for the tech industry, partnerships between partisan consultants and digital communication platforms should be considered problematic, especially given Meta’s ongoing improprieties regarding foreign interventions and disinformation. During the 2016 election, Russia was able to run a successful advertising campaign with the goal of splintering the American public. Additionally, Trump campaign manager Brad Pascale was working closely with Facebook employees to generate pointed advertising campaigns based on Facebook’s user data. Both of these factors were instrumental in Trump being elected president that year. Once this information became public, Facebook committed to making improvements to its infrastructure in order to better combat these issues in the future. But as pointed out by Siva Vaidhyanathan in Antisocial media: How Facebook disconnects us and undermines democracy, “Facebook made only cosmetic changes to its practices and policies that have fostered anti-democratic– often violent– movements for years… It pumped up its staff to vet troublesome posts but failed to enforce its own policies when Trump and other conservative interests were at stake” (p. 245). Facebook continues to be a hotbed for conservative talking points, with personalities like Ben Shapiro, Franklin Graham, and Dan Bongino consistently generating impressive rates of engagement. We live in the era of an attention economy, and increased demand for information will lead to an increase in supply of said information. Facebook’s bread and butter is user engagement, and with conservative pages consistently performing well, it is easy to assume that conservative users are a key demographic to which Facebook would cater. The TikTok smear campaign aside, Meta further entangling itself with conservative interests should raise some eyebrows. Mark Zuckerberg often touts Facebook as a neutral vessel of information, but by enlisting partisan consultants to manage its affairs, Facebook’s dealings are lightyears away from Zuckerberg’s claims to neutrality. By Kaitlin Miller, Ph.D.

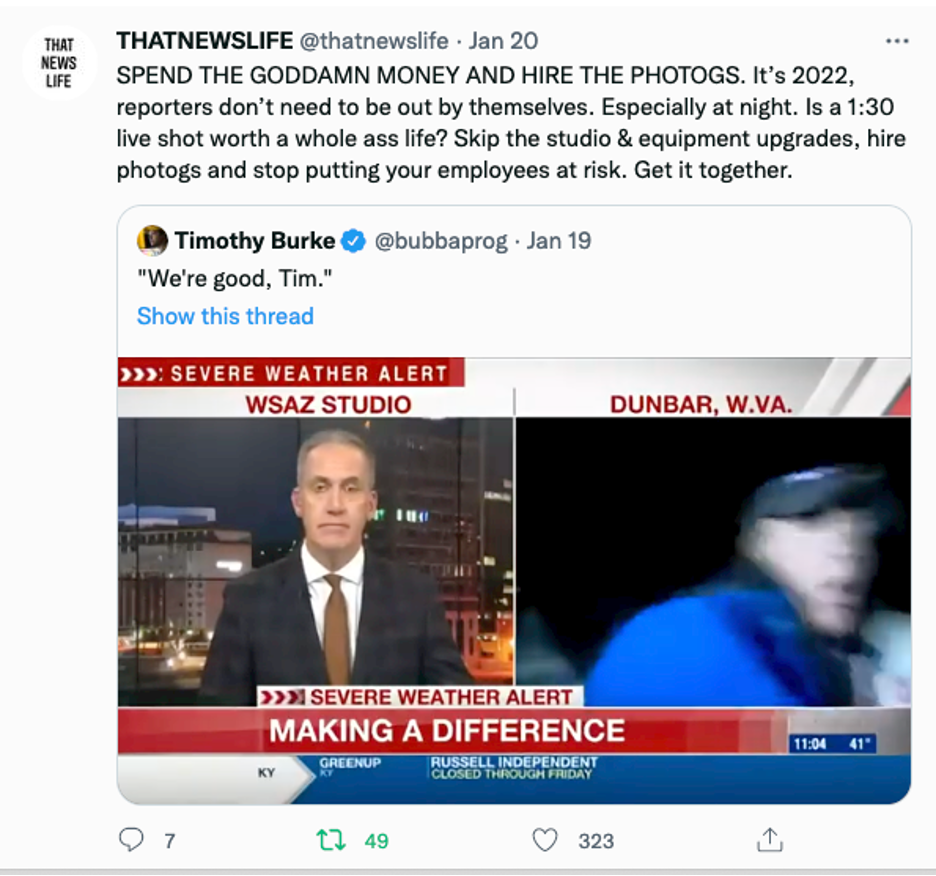

On Wednesday, January 19, 2022, local TV reporter Tori Yorgey set up her tripod, camera, live pack, and lights, and prepared to go live on camera during her coverage of a water main break. She later reported in a televised interview on her stations newscast, “I was just on the pavement… I wasn’t actually on the road. I was getting ready to talk to you and next thing I know this big SUV hits the side of me.” After the impact, Yorgey fell to the ground, pushing over her camera. Without cutting away, the video continues to roll as she is heard saying off camera, “Oh my gosh, I just got hit by a car but I’m okay.” Yorgey proceeds to fix the camera, assure the driver of the car that she is okay, and then finish her report on the water main break. The video of the incident went viral online, with coverage of the event popping up overnight. NBC news reported, “TV reporter struck by car during live broadcast gracefully rebounds to finish shot.” The Washington Post headline read, “WSAZ journalist Tori Yorgey hit by car on live TV, finishes broadcast.” And CNN’s headline? “Reporter has surprising reaction after being hit by car during liveshot.” But perhaps the New York Times said it best, “West Virginia Reporter Is Hit by Car on Air, Striking Nerve With TV Journalists.” Indeed, for many journalists—and former journalists like myself—this viral incent caught on camera did strike a nerve. While the reporter’s resilience to stand up and continue reporting is perhaps commendable, the situation itself was one that journalists felt shed light on a larger issue in the field. You see, Yorgey was reporting alone when she was hit by the SUV. TV journalists who report, write, film, and edit their work themselves have earned the title of Multimedia Journalist, or MMJ for short. This includes—for many—doing live shots alone. This practice saves money by not having to hire a photographer, but also creates what many say are unsafe working conditions. And this debate is not new. In 2018 I interviewed 19 women journalists who work in broadcast on-air. Many of them were MMJs, as I once was. As one women noted in our report “my biggest concern is that MMJs, true MMJs who are out alone, and this freaking stupid thing of MMJs doing their own live shots, which is so unsafe, is not okay” (p. 93). Another journalist noted in an interview that when covering a political rally, a U.S. Congresswoman pointed at the press area and said the “they’re fake news media.” That is when the journalist told me, “she made me feel like I was in danger at that point, because that's when people started pointing at us, booing at us and we had profanities yelled at us. And the cops even came kind of closer to us to block them from getting to us. So it was just, that was another wake up call for me. I can't be an MMJ anymore, I just can't. Because it's not even safe to do.” Indeed, many people have posted comments on Twitter threads and in Facebook groups saying Yorgey should have been wearing a reflective jacket, or that her station should have cut from her live shot sooner. But the issue for many—the nerve being struck if you will—is that Yorgey was alone. For many broadcast journalists, the battle cry is one in which they argue this reporter should have had a photographer with her. One who can survey the surrounds and provide safety in numbers while she is distracted by a director talking in her ear piece (i.e. an IFB), lights are blinding her, and she is remembering what to say once cued. The issue is simple: that she never saw it coming. When I was an MMJ, I worked night side, which is what journalists call the evening news shift. This means my live shots were always by myself, and always in the dark. I have had people come up and touch me while I was live on camera. I have had cars drive around me and rev their engines, while I was setting up, and again, by myself. I was flipped off, called names, and once even had an animal pop out of a bush, as I reported alone in a parking lot. My boyfriend, and now husband, went to work with me once and almost fought a drunk person who was messing with me while I was live on TV. I never even saw the near altercation. Again, herein lies the issue. I never even saw it. A journalist I interviewed for my dissertation research told me, “I'm always thinking about [safety]. Especially like when I'm MMJing, I don't have someone watching my back when I'm looking at the camera and I'm pressing record. I always have to watch to make sure. I'm always looking over my back. Like, ‘Hey is anyone going to come jump out behind me and try to do something or say something they shouldn't’.” This leads me to ask, while Yorgey herself said she was not hurt physically, what about mentally? Fear is a strong emotion that can have negative effects on journalists personally, and their work broadly. One can simply not look over their shoulder all day without a mental impact. As a print journalist told me once, “I worry that, you know, I, I've thought about it someday. Somebody is just going to blow me away on the sidewalk because of what I write.” Whether the issue is an SUV you never saw coming, or a person trying to assault you while you are alone, being an MMJ comes at a cost—and broadcast journalists appear to be tired of it. That News Life, a popular account aimed at sharing the work and stories of TV journalists, noted in a tweet “SPEND THE GODDAMN MONEY AND HIRE THE PHOTOGS. It’s 2022, reporters don’t need to be out by themselves. Especially at night. Is a 1:30 live shot worth a whole ass life? Skip the studio & equipment upgrades, hire photogs and stop putting your employees at risk. Get it together.” For many broadcast journalists, Yorgey’s story may have been a freak incident, but one that sheds light on the increasing danger of reporting alone. These journalists—and scholars like myself—argue the MMJ model is simply outdated, unsafe, and driving journalists to leave the industry. The hashtag #EndSoloLiveShots is being echoed among journalists online, who are tired of feeling unsafe. While the MMJ model has been hailed as the stage in one’s career where they must “pay their dues,” many say it is really the result of company greed for news organizations too cheap to hire additional staff. They suggest reporting alone, especially during live shots, requires a restructuring of investments into staffing. As one TV journalist noted on Twitter, “WHY ARE REPORTERS WORKING ALONE, ESPECIALLY ON LIVE SHOTS??? I only had to do this for 8 months, and I said never again… and I won’t. She’s lucky she’s alive. Profits over people have to stop. You can’t report the news if you have no one to report it. #EndSoloLiveShots” (@gretchen_news). My sincere hope is this incident pushes news organizations to rethink the MMJ model and staffing priorities. However, the headlines that praise this reporter for being resilient make my optimism for true change low, as they are missing the heart of the issue: she never saw it coming. |

Notes by our membersPosts on timely events by OPCaM members. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed